Beating The Heating: How to Prepare your Body for Training and Racing in Hotter Weather

Prepping for heat early can make your race day all smiles (handups from your daughter help, too)

Who hasn’t struggled through a surprisingly hot race, one that was supposed to be mild but then flared into the 90s Fahrenheit on race day? Or maybe you know you’re traveling to a hot race (Kona, any race in Mexico, or maybe even Coeur d’Alene in the usually cool and wet Northwest) but you aren’t sure how much heat acclimation you should do, or how to do it? Managing your core temperature can be the most important piece of non-training preparation after practicing race-day nutrition, and dealing with heat will only continue to become more important as races and athletes struggle to deal with the realities of climate change. Today we’ll give you a sense of how to acclimate and acclimatize (those are different?) and what you can do on race day to give yourself the best chance of keeping your literal cool. As one of our co-founders likes to say: “You can’t uncook a turkey.” Don’t be an overcooked turkey, okay?

Understanding Plasma Volume, Sweat Rate, and Cooling

Before we get into our tips for preparing, we have to take a brief detour through some physiology. First of all, how does the body cool itself in the first place? Without these processes, your body would heat up by about 2° C every minute of exercise, which would make any kind of effort beyond a few minutes lethal to humans. Happily, we seemed to have evolved to avoid that quick and ugly fate. One of the main mechanisms for cooling is sweating. A warming body sends more blood to the capillaries under the skin, where heat can radiate into the air around you. In addition, you begin to sweat; the body’s goal in this case is to cool the body by evaporation: the sweat carries energy out of your body and into the atmosphere around you. So sweating a lot is good. Sweating, however, dehydrates your body, which eventually will contribute to temperature rise. Why is this? Well, your body has a kind of internal lake, and if you remember specific heat from 7th grade science, you remember that the bigger a body of water, the longer it takes to warm that body of water up. Our internal lake is everywhere, part of that “the human body is 70% water” cliché that floats around, but one of the parts we can manage is our Plasma Volume, or the watery component of our blood. The other part of our blood are the red blood cells, those inner-tube-shaped discs that keep us alive by transporting everything we need around the circulatory system. Plasma is a yellowish but clear liquid that the red blood cells are suspended within—without plasma your blood would instantly coagulate in your veins, which would be…suboptimal for continued living. WHY IS THIS IMPORTANT? Well, you can increase your plasma volume ahead of your event through several different ways which we’ll cover below, but if you’re paying attention you’ll remember that a big body of water warms up more slowly, and your plasma volume is a big part of your internal lake. Therefore, if you have more plasma volume you’ll heat up slower, and cooking your turkey takes longer. So our big three goals in preparation for hot events are:

Increase capillary density so more heat can radiate away

Increase plasma volume to slow heating and to stave off dehydration

Increase sweat rate to improve cooling through evaporation

Ready? OK, let’s begin.

Acclimation vs. Acclimatization

First of all, let’s get some terminology out of the way. Acclimation is the process of preparing your body through different techniques to better handle the heat. You might sit in a sauna, pedal your bike in a hot room, hit the hot tub after a hard swim (gross), or wear too much clothing on a warm day, all of which will raise your core temperature and incur the changes we’re after. Acclimation is something you do in the weeks and months before the race, and it doesn’t look much like the actual race. Acclimatization, on the other hand, is a much more specific process that entails training in the exact conditions of the race. For most athletes, this is difficult or impossible, since it’s unlikely you’ll be at the race site for weeks and months before your event. We call out this difference because we believe that, in general, workouts should not be race day rehearsals, except in tiny doses. Acclimatization takes a while, too, and if you don’t acclimate first, you’ll simply deplete your body by trying to acclimatize race week. Don’t be like those athletes who think they can adapt to altitude by going the race a week ahead of time: true acclimatization takes weeks if not months, and to be successful you need to acclimate first and acclimatize later. OK, vocab lesson over.

Start Early and Periodize/Dose

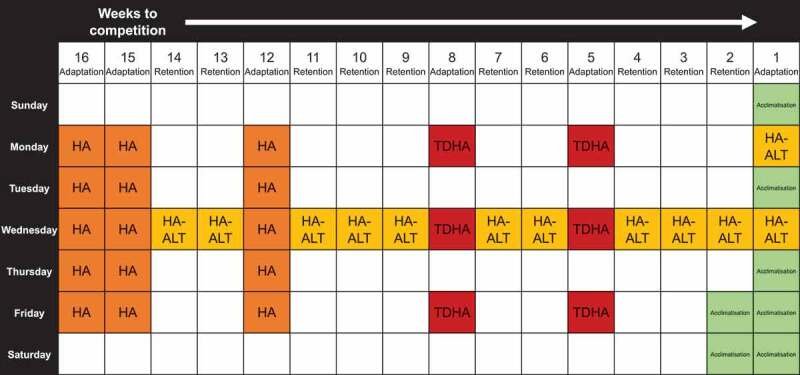

Continuing in our theme of saving endurance athletes from themselves, we encourage you to start your heat training early. In a meta-analysis of athletic preparation ahead of the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, the study authors found that most athletes began their heat acclimation 16 to 20 weeks before the games, suggesting that this is something you should include long before you head into your race-specific period. But we all know that endurance athletes LOVE to overdo things, and we don’t want someone to read this and then resolve to hit the sauna every day, twice a day, for hundreds of days before racing. Your body is wildly complex and adaptable, and if you convince it that it now lives in a hot environment, your plasma volume will expand at first but then eventually return to homeostasis (baseline), rendering your efforts moot! Don’t overdo it, endurance athletes! Heat preparation appears to work in a similar way to altitude training, where athletes perform doses of heat exposure coupled with weeks of heat maintenance. We suggest a pattern of two weeks of heat exposure, where athletes do some kind of heat work four-to-five times a week, followed by a week of maintenance where you do heat work only once. Hear that, everyone? Only once! More is not more in this context! Here is a sample protocol, below, with explanation:

“Proposed 16-wk chronic heat preparation approach which includes MTHA (medium term heat acclimation) of ten 1/day heat acclimation (HA) sessions commencing 16 wk prior to competition start, followed by short term heat acclimation (STHA) in the form of five 1/day HA (12 wk prior to competition start) and then twice-daily heat acclimation (TDHA) 8 and 5 weeks prior to competition start). Weekly adaptation retention sessions using established exercise heat acclimation approaches e.g. isothermic method (HA) or alternative approaches (HA-ALT) e.g. over-dressing or post-exercise hot water immersion (HWI)/Sauna, punctuate these interventions. Days with no notation are regular training/recovery days. Athletes may consider implementing double sessions e.g. strength and conditioning or similar activity on acclimation days.”

Raising Core Temperature is King

The big goal with heat training is to raise your core temperature, which will raise your skin temperature. Once you’ve inflicted that stress on your body, it will try to find ways to adapt, shifting blood to the skin, sweating more, and boosting plasma volume. How much should you raise your core temperature? Well, unless you have access to a swallowable thermometer OR a very good friend who is willing to take, um, internal readings, you probably won’t be able to track this exactly. BUT it doesn’t really matter. Any of the following mechanisms will raise your core temperature, so if you stick to these you’ll achieve your goal:

Training in a hot and relatively dry room: examples include riding a bike at 50% of threshold power in a 100° F room for 90 minutes; rowing for 40’ in a room at 40 C and 60% relative humidity

Passive heating: sitting in a 180° F sauna for 20’ after a workout of at least 30 minutes; sitting in a hot water (100-110° F) bath up to your neck for 15-20’ after a workout of at least 30 minutes

Overdressing during training: wearing long sleeves, tights, etc…while doing your training in a normal or warm environment

What does all of this accomplish? Well, we’ve pointed this out above, but endurance athletes love lists, so…here you go. The adaptations from raising your core temperature are:

Hypervolaemia (higher water content of blood, basically)

Lower perception of discomfort/effort/fatigue

Lower core temperatures during prolonged exercise

Decreased glycolysis/increased fat oxidation (this is huge for endurance athletes, as it means you have more fuel for longer)

Higher plasma volume, which leads to…

...higher stroke volume, which can lead to higher VO2max (but not necessarily) and…

…slower dehydration, which is what we’re really after

Lower resting heart rate

Lower exercise heart rate

Increased blood skin flow, which leads to…

...higher sweat rate = more cooling

Enjoy the sweat!

Sweat is Your Friend

So, sweat. It can seem that sweat is the enemy, since it carries fluid and electrolytes out of your body during exercise, and it would seem that retaining as much of those as possible would be important. But as we’ve pointed out above, more sweat equals more cooling, so we really want to encourage sweating. But now we need to account for how much fluid you lose during sweat. If you’ve been with us a while, you’ve seen us talk about the sodium content in your sweat, a crucial number to know for endurance athletes. If you know how much sodium you lose per liter of sweat, and then you know how much sweat you lose in a given time period, you can make a plan to replace as much of that fluid and electrolytes as possible! So take the time and get a sodium content test done, and then test your sweat rate on your own time. How do you do that? Simple:

Before a workout, weigh yourself naked and dry (weight A)

Keep track of how much fluid you drink during a workout

Weigh yourself naked and dry after the workout (weight B)

Subtract weight B from Weight A to find the difference and convert to fluid ounces or milliliters (1 pound = 16 fluid ounces, 1 kg = 1,000 ml)

Add the volume of the fluid drunk during the workout

Divide that total volume by the number of hours in the session to get your sweat rate per hour

Ideally, you perform this test several times in the run up to your event, seeing your sweat rate rise as you get closer. If your sweat rate is going up, you are successfully acclimating.

Fitness Helps

Remember reading above that more capillaries improve your body’s ability to get rid of heat? You know what generates more capillaries throughout your body? Effective aerobic conditioning, otherwise known as easy-to-moderate training. Don’t skip this work, as it is the golden goose of endurance sport—it is truly the gift that keeps on giving. The fitter you are, the better your radiator is at getting rid of heat, so…do those long easy rides, runs, and swims!

Campeche, Mexico, where not only is it usually hot but the race often starts at noon!

For the Ladies

As always, ladies, the men have it slightly easier in this context. That sucks, but it doesn’t mean you should throw up your hands. The takeaway is essentially the same as everything we’ve said thus far, but knowing the why is always powerful. Racing during the luteal phase (high hormone phase, right before menstruation) of your cycle can be more difficult, as core temperature rises faster during that phase (although how much this affects performance is still unknown). It seems like this can be mitigated by heat acclimation and adequate fluid intake. Hormonal contraception can also raise core temperatures AND lower sweat response, both negatives in this particular scenario. What’s the big takeaway for women? You should perform acclimation work during all phases of your cycle, and women may benefit from a longer term (more than ten days) acclimation program than men will.

Conclusion

Just this week warm weather returned to the Pacific Northwest, where Campfire makes its home, and we have a summer of warm racing ahead of us. Don’t worry if you haven’t started acclimating yet—there is still time! Begin adding some heat sessions to your training, and some of that will happen naturally as you perform your workouts outside in the glorious temperatures. If you start acclimating, you’ll be better prepared for warm days when they coincide with race day. This doesn’t mean that if you are heat acclimated you won’t have to modulate your pace at all, but you’ll certainly have to modulate it less than you would if you hadn’t prepared. As with most things in endurance sports, proper preparation prevents poor performance. With that monument to alliteration out of the way, we’ll leave you to it!

Sources

Gibson, Oliver R et al. “Heat alleviation strategies for athletic performance: A review and practitioner guidelines.” Temperature (Austin, Tex.) vol. 7,1 3-36. 12 Oct. 2019, doi:10.1080/23328940.2019.1666624

Golich, Lindsay, MSc. “Heat and Humidity Preparation for Extreme Training and Racing Conditions.” Endurance Exchange, January 2022.

Garrett AT, Creasy R, Rehrer NJ, Patterson MJ, Cotter JD. Effectiveness of short-term heat acclimation for highly trained athletes. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2012 May;112(5):1827-37. doi: 10.1007/s00421-011-2153-3. Epub 2011 Sep 14. PMID: 21915701.

Garrett AT, Goosens NG, Rehrer NJ, Patterson MJ, Cotter JD. Induction and decay of short-term heat acclimation. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2009 Dec;107(6):659-70. doi: 10.1007/s00421-009-1182-7. Epub 2009 Sep 1. Erratum in: Eur J Appl Physiol. 2009 Dec;107(6):671. Rehrer, Nancy G [corrected to Rehrer, Nancy J]. PMID: 19727796.