Setting Up Your Devices for Endurance Success

One of the BEST uses of your smart devices

Put your bike computers and smartwatches to work for you…not the other way around

I remember one of the hardest workouts I’ve ever done: a set of 1600s and 800s on a flat, unshaded bike path along the shore of a Floridian lake, the air heavy with humidity. Our coaches had sorted us into groups and given us times to hit for each interval, and we set off, packs of five or six leaving from our arbitrary start line (a chalk line drawn in the shadow of a huge myrtle tree, the last respite from the sun we’d have until completing a mile or a half-mile) and either running down and back for the mile repeats or just down for the half-mile repeats. The workout was going well. I felt focused on my effort internally, my outward focus gathering in the lake, the heat, and the athletes around me. One of those athletes, annoyingly, raised her smartwatch to her face roughly every six strides, searching for confirmation that she was executing the interval to perfection.

I tried to ignore it, but a call-and-response kept cycling through my head “Gosh, do you really need to check your watch again? Chris, chill, do YOUR workout, don’t worry about it…my god, AGAIN?!” I began to worry that the obsessive lifting of the watch would have a long-term effect on the muscles of her left arm and shoulder. I didn’t say anything, because she was not an athlete with whom I work, but I couldn’t help but notice that this particular athlete approached most of the workouts at camp in the same way: trying so hard to make each interval perfect that she never seemed to notice anything else going on around her. Even though we were training outside, in the company of other athletes we liked and respected, she may as well have been doing her workouts on a treadmill, in Watopia, running past the virtual ghosts of other Zwifters, an avatar of alone-together behavior.

Modern training devices have done quite a bit for us as athletes. These days we carry powerful mini-computers on our wrists or bike stems, smaller versions of the supercomputer phones we also carry with us on workouts, in their own turn the shrunken siblings of the massive devices that hulk out on our office desks or living room credenzas. But the devices can promote a whole host of unhelpful behaviors for endurance athletes (just as phones pose risks to those of us who use them all the time). Today we’re going to work through some of the best practices for smartwatch and bike computer use. We believe that by using our devices to contextualize our efforts, rather than allowing them to drive or lead our workouts, we can become faster, happier, and healthier athletes, the Campfire goal.

Workout data contextualizes but doesn’t direct

Whoa, hold the phone, what the hell does THAT particular idea mean? Bottom line up front, it means that your workout data should be secondary to how your body feels and what your perception of effort is. We have all experienced heading out for a hard workout, like 5x1600m at the track, or 3x20’ @ FTP, only to realize that—even though our bodies feel the correct level of effort—our output (speed, power, pace) is not meeting the goal that day. On those days, have you had more success by gritting your teeth and trying to force the workout to perfection, or have you listened to what your body is saying and work more in the spirit of the effort, rather than the prescribed effort? I’m sure a few of you will try to convince us of the “no pain, no gain” route, but what we’ve found is that letting the numbers dictate success or failure, rather than listening to your body to tell you how hard you can go today, is a smoother path forward, less littered with injury and burnout. On the other hand, simply telling you to go out there and train by feel is irresponsible, too. Doing that is like handing a kid a violin and saying “What, you can’t just play that?” A large amount of practice needs to happen before you can hear accurately what your body is telling you, and your devices, if you set them up correctly and employ some best practices, can get you to that point of “just playing” faster.

How devices can help you get better through contextualizing effort

Many athletes have heard or seen the four stages of competence, which move from unconscious incompetence to unconscious competence, making stops at conscious incompetence and conscious competence along the way. When many of us start out in sport, we’re doing the sport simply because we like it and it’s fun. Maybe we have some natural aptitude, maybe we’re the Swedish Chef on skates, but at this stage we may not even WANT to get better. We make mistakes but we don’t care, because ignorance can be bliss. Usually, if an athlete does want to get better, a device at this stage can help us see the error, pointed out by a helpful coach or mentor: “Hey, see this section of your ride? This, right here, is why you didn’t run well—you were riding way too hard. It’s OK, don’t beat yourself up about it, you didn’t know! You’ll know to avoid that mistake in the future.” Now, armed with that information, our athlete spends a few weeks training, exploring their efforts and listening to how their body responds. Maybe they discover that at 200 watts their breathing gets too labored, and that when their breathing was that labored in the race their coach told them it was too much. Or maybe they use heart rate, and know now that efforts over 160 beats per minute (BPM) will leave them walking before the end of the run. The athlete goes to their next race and…gets it wrong again, but this time they return to their coach and say “Man, I could see I was over the effort again, but I felt so good! I didn’t think it would leave me walking again!” They saw their mistakes but made them anyway at this stage, the conscious incompetence phase. Next, having learned that their actions have real consequences for their body and their desired goals, the athlete sticks to the plan exactly, watching the watts, pace, or heart rate like a hawk during races and workouts, and results are…better but not great. What’s happening? This athlete, at the conscious competence phase, is hitting their prescribed numbers, but still something isn’t quite right. They come back to the coach with a quizzical expression on their face.

ATHLETE: “Well, I did stick to my numbers, and the race went better than I thought, but…I just felt as if there was more to give.”

COACH: “Ah, great! First of all, congratulations on the race! Can you describe to me the physical sensations of riding at the wattage that led to a successful run?”

ATHLETE: “Suuuurrrrre…maybe. OK, well, my breathing: it was deep but it wasn’t gasping.

COACH: “Great. What else?”

ATHLETE: “My legs felt the effort, but I really felt like I was on top of the pedals—that was that feeling of having more to give, you know? Like I could have really stomped on them.

COACH: “But you know what happens when you do that, remember?”

ATHLETE: “Yeah.”

COACH: “OK, so you felt the effort, but you felt as if you could do more. Was there any pain, or strain, or burning? How uncomfortable was it?”

ATHLETE: “It was uncomfortable but manageable.”

COACH: “GREAT! Love that. OK, anything else?”

ATHLETE: “I felt in control.”

COACH: “Awesome. OK. Here’s what we do. Now when you go out for a workout, you know those are the rough sensations you should feel at that wattage: deep breathing but not gasping, on top of the pedals, more to give, uncomfortable but manageable. When you feel those sensations, you know you’re in your ‘racey’ area. The next time we do race pace intervals, I want you to aim for those sensations, and use your bike computer as a backstop. The numbers you see certainly shouldn’t be perfect, but if they are within 5% on either side of what we’re aiming for, that’s more than good enough.”

Finally, when the athlete attains the unconscious competence phase, they simply head out onto the bike course and let their experience and feelings guide them. Athletes at this stage often don’t even need to look at their bike computers, checking the race or workout afterward to cross-check their work and make sure they’re in the range. And guess what? As the athlete gains fitness and ability, they’ll see their numbers going up at the same effort? Is this a problem? NO! THIS IS THE THING WE ARE AIMING AT THROUGH TRAINING! HIGHER OUTPUTS (SPEED/POWER/PACE) AT THE SAME EFFORT (HR/RPE).

Device setup for achieving unconscious competence

TURN OFF AUTO LAP. You hear that, all of my athletes? Please, please, please, for my sake and the sake of the coaches you will work with after you fire me, TURN OFF AUTO LAP for your training. You can turn it back on FOR THE RUN ONLY during races, but other than that please turn it off. Your coaches want to be able to quickly see the intervals you did in your session. If you have intervals, your button-pushing looks like this: START, LAP at the beginning and end of each interval, STOP. That’s it! Same thing on the bike.

WEAR A HEART RATE STRAP. Oh please, wear a HR strap. The optical HR just isn’t there yet, and straps are almost a half-century old by now. They work. Find one that fits and doesn’t chafe (you just have to try several, I’m sorry, that’s it) and wear it IN EVERY SINGLE WORKOUT that’s not in the pool. Yes, you read that right. EVERY. SINGLE. WORKOUT.

YOUR GPS DEVICE IS INACCURATE ON THE TRACK. Yup, you read that right. Your $600 watch is mostly useless on the track, due to the fact that satellites don’t like decreasing radius turns. But why, why, why are you thinking about using GPS pace on the track? You literally have a digital watch on your wrist and tracks are pretty much universally 400m in distance. If your coach wanted average pace efforts on the road, they’d send you, well, out on the road. On the track we want the time (which you can get by hitting lap at the beginning and end of each interval), the distance you know because of basic math, and the average HR of the interval. CAVEAT: yes, some devices now have a “track mode” which does a little better with getting distances right, but…why? We really don’t get this one. Run your interval distances, hit lap at the beginning and end of each of them, and…that’s it. Nothing else to set up, trouble-shoot, or futz with while literally running almost as fast as you can. You don’t want your attention divided on track days. Devices are cool, yeah, but know what’s cooler? Nailing your track workouts. Strava doesn’t care, but your physiology sure does.

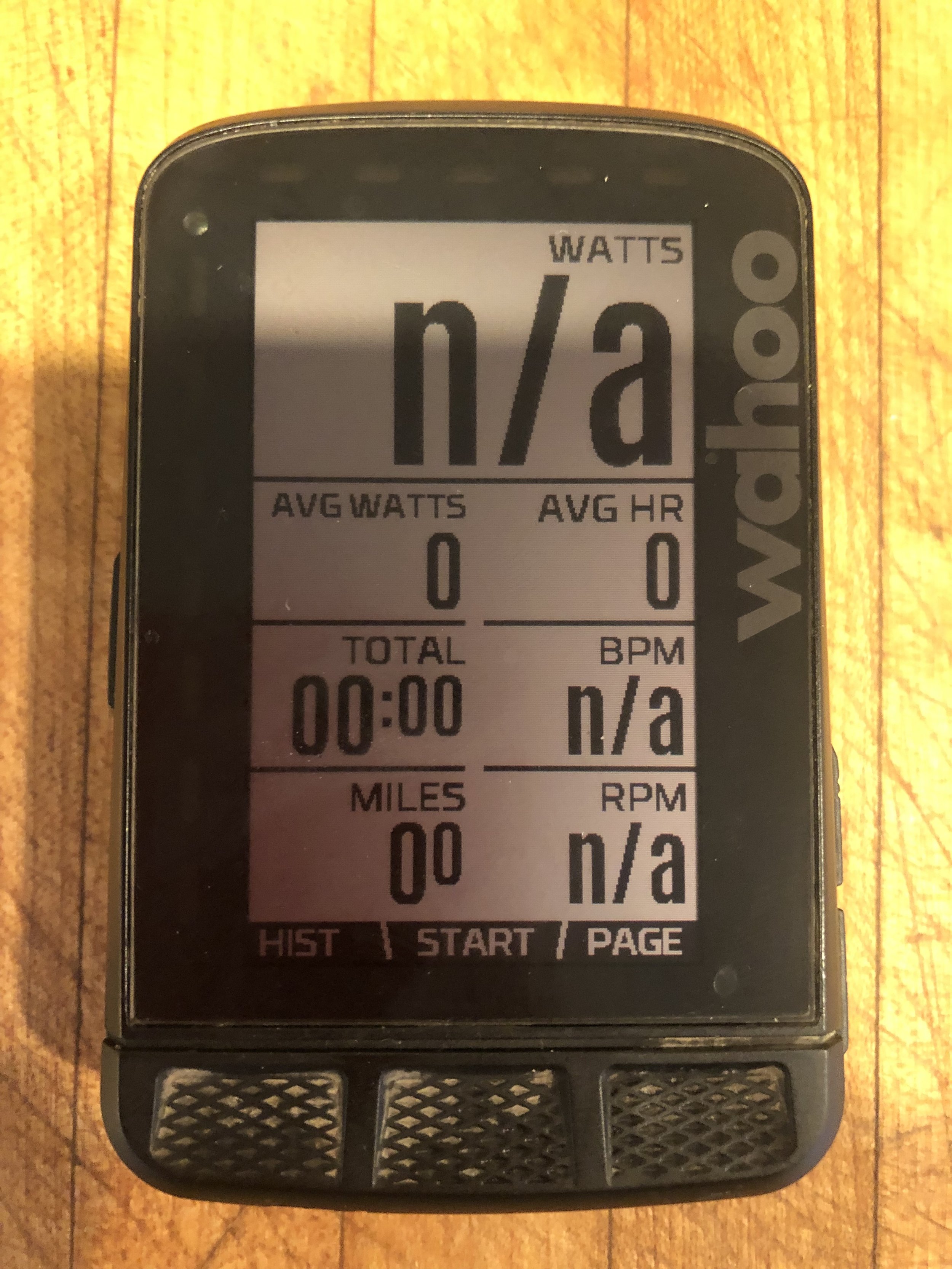

Page One, Bike: your global data screen on the bike, and the one you’ll use while racing. Real time watts (if you don’t have a power meter, real time HR goes here), average watts and HR to make sure you’re not over- or undercooking your effort, time (since race brain is a real thing) real time HR, distance, and cadence.

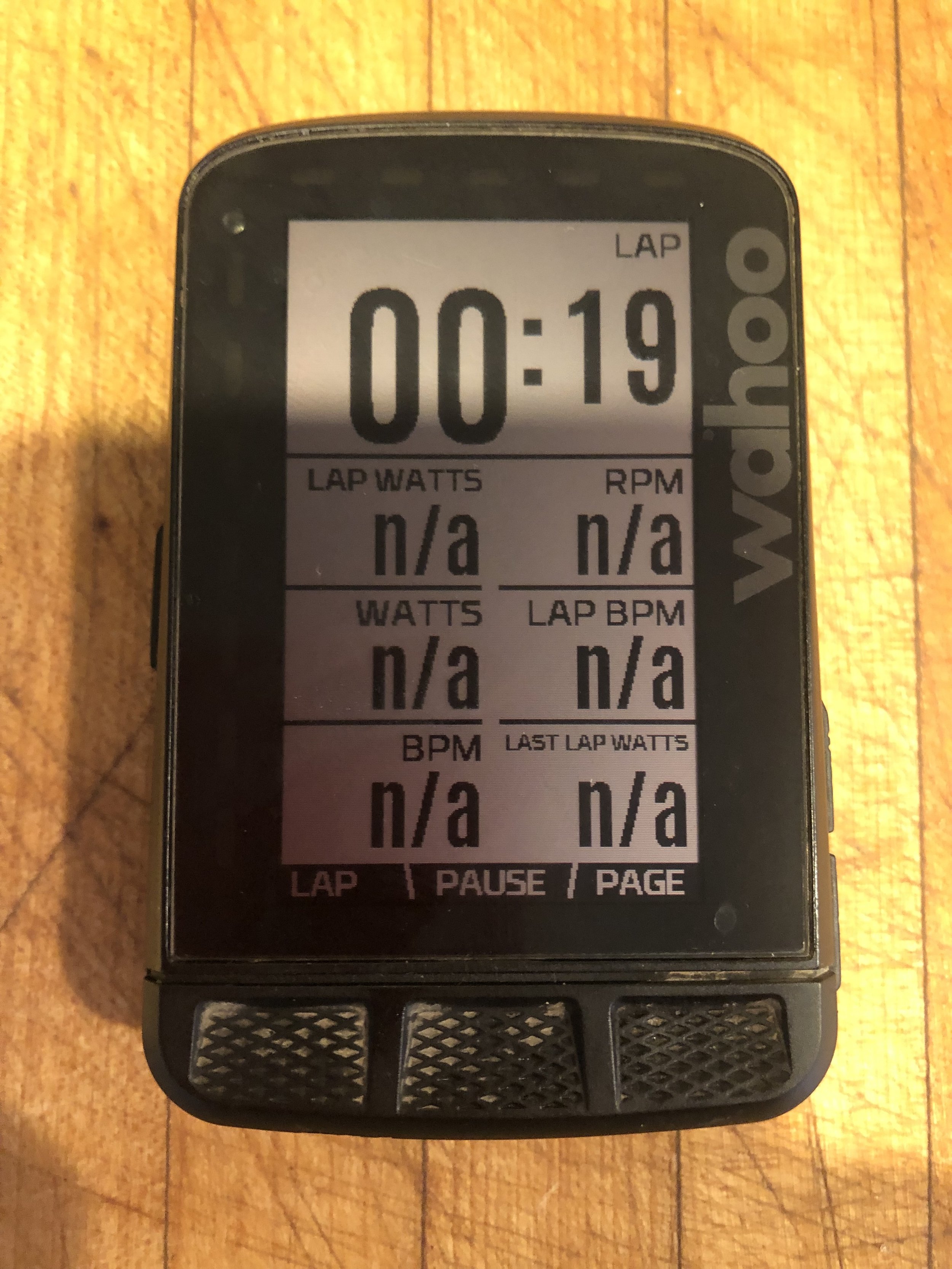

Page Two, Bike (Interval Sessions): lap time (it’s generally helpful to know this if you’re doing timed intervals, we think), lap wattage and HR, real time watts and HR, cadence, and last lap watts, so you can see how you did when you’re not slavering all over the screen.

Page One, Run: your global data screen on the run. Workout distance and time, average pace, and present HR. Everything you need to eyeball how you’re doing.

Page Two, Run (Interval Sessions): lap distance, lap time, average pace for lap, and average HR for lap. It can be nice to have real-time pace here to keep you from overcooking the pace in order to bring the average pace into line, but you’ll quickly learn how to do this by feel.

Page Three, Run (Racing): the GOD page. Simply real time HR, and lap HR. When you race, you can turn auto-lap back on, and you’ll be able to see your average HR for each lap and your real time HR. Since virtually 100% of the best endurance performances in the world (go look it up) come from a negative split EFFORT (not pace), this is all you need to look at during a race to have your best day. Looking at pace on race day will generate a quick trip to the struggle bus, since it is literally out of your control. The only thing you are in control of? Attitude and effort. Attitude can be covered in another piece, but HR is a great reflection of your effort. If you need proof, think of the last time you tried to run up a hill at the same pace you were just running on the flat. Pace may have stayed the same, but effort would have gone way up. Since we’re mostly managing effort in races, and we aren’t in control of the course and the conditions, we just don’t need to track pace. It will likely work against you, actually, and keep you away from unconscious competence.

Set up alerts. Just like the one at the top of this piece, setting alerts that remind you to drink or eat are really helpful, since it outsources something many athletes forget to do on race day.

Don’t bring your watches to the pool. This one deserves its own post, but really, stop it. You can all count to sixty, which is the longest interval a coach will probably prescribe you (that’s a 1500, and you can also hear the heads of all non-Americans exploding because they swim in normal-sized 50m pools, which is just 30 lengths instead of 60). Stop luxuriating in your claims that you can’t count to eight or twelve or sixteen. The watch in the pool is CLASSIC dissociative thinking, in which the athlete basically removes themselves from the situation and lets the watch do the work, a lot like our athlete at the top of the story. By counting your laps, you will be focusing on your effort and how your body feels; you will be associating with the workout, which is a powerful move in achieving flow state. Counting your laps is like counting breaths in meditation, or counting steps in a difficult run—the small amount of background thinking actually crowds out distracting thoughts, and this very often leads to flow states, in which athletes have great, unconscious (there’s that word again), performances.

So that’s it! Devices are fun, and sexy, but really they should exist primarily to record data and to contextualize your effort, so you know in your body what 200 watts feels like, or 7:30/mile on a flat road, or 160 BPM while running up a hill. Don’t get stuck inside your watch during races and training, like all of those tourists who spend their vacations behind their phones, taking pictures, and missing life for the recording of it.