HOW TO USE THE SWIM CLOCK AS A TRAINING TOOL

UNDERSTANDING “SENDOFFS,” “RED MIST,” AND REST INTERVALS

by Chris Bagg

Triathletes are busy people. We often say at Campfire that Triathlon is less a sport of true physical demand and more one of logistical demand—being passable at THREE endurance sports at once requires a huge amount of time and energy, and due to that triathletes tend to be amazing at cramming a lot of activity into a small amount of temporal space (time). Chances are you are the best person in your peer group at getting showered and changed. If you’ll permit a small digression in service of our larger message today, think of the last time you ran some errands. Maybe you needed to get to the dentist, pick up some groceries, and then grab your kids from school. Here’s what each of those might take, timewise:

Dentist: one hour

Groceries: 45 minutes

Waiting for kids in pickup line: 20 minutes

OK, that’s a total of two hours and five minutes. You need to pick the kids up at 3pm, so you need to leave the house at 12:55, right? Right?

We’re leaving some white space above for your laughter. OF COURSE that won’t work. There is transportation time, mistake time, and “oh crap something just came up time,” only an 18 year-old would think he could cram all three of those activities into the time that they would take to perform them. Oh, and doing so would be enormously stressful, too. You wouldn’t feel good while trying to accomplish the impossible, and you’d feel enervated and disappointed afterward.

Since we’re not a personal planning company, why are we talking about this? Well, we are here today to communicate the concept of a sendoff or pace interval while swimming in the pool, and how you can manipulate those time frames to achieve the training goal of the workout OR to design your own stimulus for training. Let’s return to our hypothetical errand trip, above. What’s a sensible amount of time for those three activities? Let’s say all three destinations are within 30 minutes of each other and home, and that your dentist appointment is at noon. Leaving 30’ before your appointment is a recipe for disaster, so let’s leave an extra ten minutes for things to go wrong, so we’re leaving the house at 11:20. Groceries are close to the dentist, but almost 30 minutes from school, so you know you need to be leaving the grocery store no later than 2:25 or so. OK…leave home at 11:20, arrive at dentist’s at 11:55 (slight slowdown on I-5, good job leaving early), appointment ran slightly over and you’re out by 1:15. Jaunt across the street to the grocery store and done there by…oh, yikes, 2:10? Quick, pack up the groceries into the car and let’s head to the school. Whew. Arrived by 2:50, which gives you a nice little 10’ nap in the driver’s seat of your car, which makes the other parents nod in empathy.

2:05 of tasks, but 3:40 in elapsed time, and you were still close. But MUCH less stressful than hoping your car is a teleportation device, and more respectful of other people’s time, too. To finally bring this metaphor to a close, you gave yourself an “interval” inside of which to accomplish your work with some additional resting time, so as to keep stress low.

A “sendoff” is the exact same thing: an amount of time you have to swim a given interval AND take your rest. So if a coach tells you “I want you to swim 10x100 on a 1:30 sendoff” (and that will usually be communicated as “ten by 100 on 1:30” with no additional information), that coach is saying you have 90 seconds to complete the interval AND take your rest. Want more rest? Swim faster and arrive at 1:15, getting 15 seconds rest. Want lower intensity? Swim easier and arrive back at the wall at 1:27, getting three seconds rest. The nice thing with sendoffs is that YOU have some say in the level of intensity.

Why?

Yeah, great question. Why do this in the first place? What’s wrong with rest intervals, like doing 10x100 with :10 rest after each one. First of all, sendoffs are designed for group swim workouts, where you may have as many as 60-70 swimmers doing the same session. If you let everyone swim their own pace and take ten seconds rest after each 100, you’d quickly have total chaos. By utilizing sendoffs, the leader of the lane keeps everything organized, leaving punctually at the end of each sendoff interval, with their lanemates following usually five or ten seconds after the swimmer in front of them. But even if you’re NOT swimming in a group, sendoffs are superior to rest intervals, and here’s why:

Keeps things on a tight leash

So imagine you’re using rest intervals, taking ten seconds after each interval. Maybe you swim that first interval and arrive back at the wall with the clock reading 00:12, or twelve seconds into the minute. Maybe you’d be good and leave ten seconds later, when the clock says 00:22, but most triathletes, we’ve discovered, like things neat and orderly, so perhaps they leave when the clock says 00:25. Or, worse yet, they are using their watches in the pool, staring at them and having to hit “lap” when they start and stop the interval. Rest intervals tend to get a little longer than their originally intended duration, which isn’t the biggest deal but does begin to introduce some vagueness into your session. We do not want vague. Sendoffs keep you on a nice, tight schedule: you know that, if you left on your first 100 when the second hand of the clock was pointing at 12 o’clock (“the top” in swimming parlance) you’ll leave for your second when it is pointing to 6 o’clock, 90 seconds later (“the bottom” in swimmer-speak). Rather than calculating the next time to leave, it’s written right into the workout, and suddenly you have a very clear timetable for this particular set.

Sets the intensity and type of session

Let’s keep going with our hypothetical set: 10x100 on a 1:30 sendoff. Let’s imagine two different swimmers, Paul and Stacy. Paul is newer to triathlon, and he’s training for an upcoming Olympic-distance triathlon. He has a goal time of 25 minutes in his race (1:40 per each 100). Stacy swam in college and competes at US Masters Swim Meets, focusing on the 1500m race, which she usually completes in around 20 minutes (1:20/100). If both Paul and Stacy try this workout, they will have VERY different experiences. The set is 10” per 100 faster than Paul’s goal race pace. It’s likely that he might be able to swim the first one in under 1:30, but it’s asking a lot of him, and it’s such high intensity he’s very unlikely to make any interval past the first one. For Stacy, on the other hand, this will be a fairly easy set. It’s only 2/3 of her race distance, and if she swims a few seconds slower than goal race pace (maybe around 1:22-1:23/100) she’ll get 7-8” race. Not luxuriant, but certainly not crushing. What would be a sufferfest for Paul is a fairly moderate aerobic stimulus for Stacy. So no two sendoffs are created equal or even close to equal, in the same way that no two swimmers are created equal. Let’s consider Paul for a second. What if we wanted a session that was more like Stacy’s experience, a moderately-challenging session that’s well within his wheelhouse? Let’s make those 100s on 1:50, so he too will get 7-8 seconds rest if he’s swimming a few seconds slower than race pace. But what if we wanted to stimulate Paul’s ability to go fast? Well, going fast requires REST. If you want to move quickly in any endurance sport, you need to be rested in order to train that system effectively. If that was the case, maybe we’d give this set to Paul:

10x100 on 2:30

Aim for 1:35-1:40 (slightly above goal pace) for each 100

You’ll get plenty of rest on this set, so go fast!

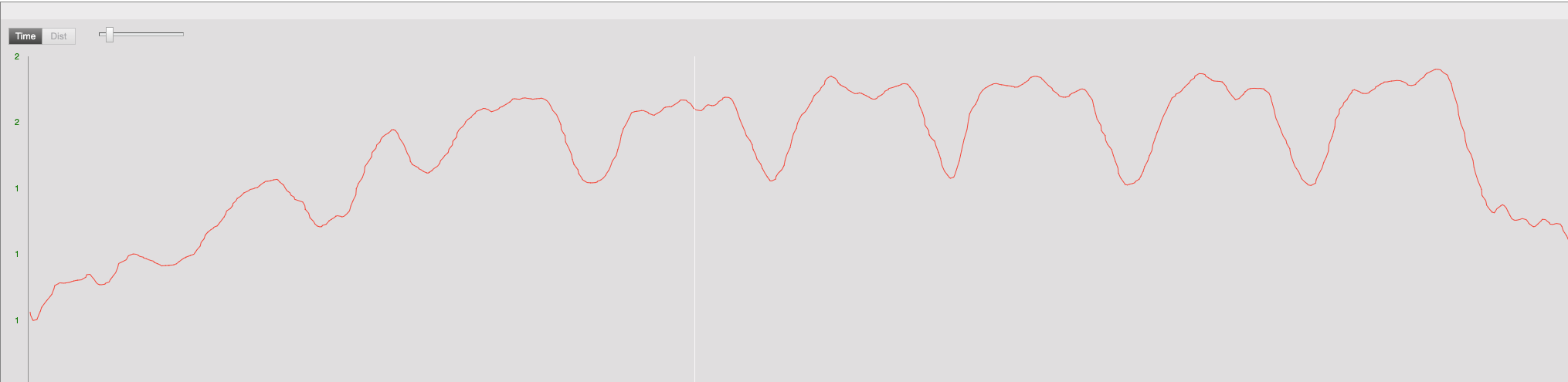

So much rest, right? This will allow Paul to recover almost fully after each interval and really hit that interval hard. If we were looking at a HR graph of this workout, it would probably look like this:

High peaks, deep valleys. This means the athlete is stressing their speed system, but then fully recovering in between. Paul would probably be breathing hard at the end of each interval, but then his breathing would calm and quite while he recovers, which is how speed intervals should work (you gotta be FRESH to go FAST). OK, let’s think about another set, maybe the most challenging thus far:

10x100 on 1:45

Aim for 1:40 (race pace) for each 100

You’ll only get a few seconds rest! Go for it!

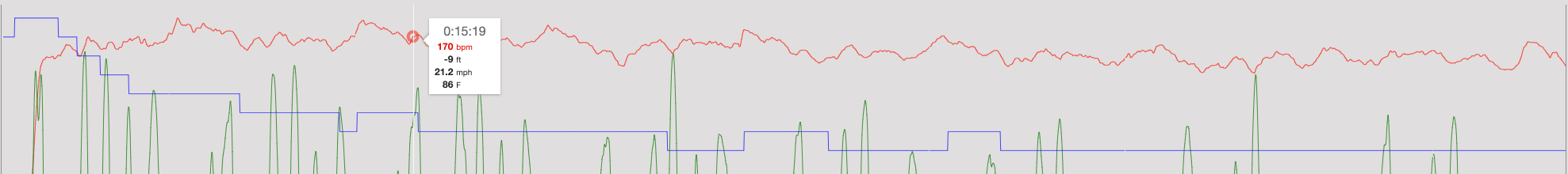

This is a challenging set, since we’re basically asking Paul to swim race pace with very limited rest. This may be a good session to do as the race approaches and our work gets specific. Paul will likely be swimming hard AND not getting much rest, and his heart rate probably looks like this:

Here we see a much steadier HR, but at a high effort, probably close to critical swimming speed (CSS) or threshold or LT2 or OBLA or MLSS or whatever else you use to denote that second threshold in your exercise intensity scheme.

If Paul were simply using rest intervals, there is a lot of wiggle room in the system. Maybe he’s feeling off that day, so he doesn’t actually swim that hard or that fast, takes his ten seconds rest, and basically has a recovery day in the pool. Using sendoffs allows the coach to send the message as to what kind of intensity they would like. If the coach knows an athletes’s threshold pace or CSS, that coach can, simply by scheduling the session, communicate the desired intensity. If your threshold is 1:30 and your coach is giving you sendoffs of 1:25/100, you know that you have a MISERABLE (and very likely not possible) session at the pool. But maybe that coach is giving you a set like this:

10x100

- Odds on 1:25 (GO FOR IT!)

- Evens on 1:40 (swim easy and just make it)

OK, now we have something of a pace change session, or maybe something like over-unders on the bike. The swimmer will have to really boogie to make the 1:25, but then they get a relatively long sendoff right away in which they can get some active recovery. This kind of session is very well suited to triathlon, because the pace changes A LOT while you are in a race and it’s good to prepare for that.

beyond basic sendoffs

Sendoffs are a great tool that every swimmer should be able to use and understand (primarily because they free you from the tyranny of your watch—please stop wearing those to the pool), but they have their limitations. Let’s imagine two swimmers that are a little closer to each other. Stacy and Brad both swam in college, but Brad has taken some time off and is working his way back to fitness. He can swim relatively the same speed as Stacy, but he doesn’t have the fitness, yet, so he needs a little more rest. Maybe Brad swims that first 100 of the same set of 10x100 on 1:30 a little faster than Stacy, but then his times begin to fall off and soon he’s fighting to simply “make” the interval (“making” the interval means finishing the interval before the sendoff elapses). He gets there, but his experience of the workout is VERY DIFFERENT than Stacy’s (her experience was fairly moderate, but his was quite hard—so sometimes even for swimmers of similar speeds, the workout can be very different. Enter “Red Mist” style sets. The other issue with sendoffs is that it’s hard to do the math if the sendoff ends with a number that is different than “0” or “5” (think of trying to do a set of 10x100 on 1:27 while using the pace clock—yikes), so you’re kinda using a crude instrument.

What is red mist?

If you want a longer, fuller answer, head here, but basically a red mist style set is one where you’re about a full gearshift below threshold pace, but you don’t get much rest. It’s a long, difficult-but-not-crushing style of swimming that is excellent for developing aerobic conditioning. When we have swimmers perform red mist sets, we use a Finis Tempo Trainer, pictured above. If we know an athlete’s threshold pace (let’s take Stacy’s and say that her’s is 1:20, or the pace she swims her 1500m races in), we split that in half to get an athlete’s “Red Mist 0” number. In Stacy’s case, that would be 40. We set the Tempo Trainer in Mode 2 to read “00:40,” and it will now beep every 40 seconds. This would be an astoundingly difficult send-off, because it would mean swimming faster than threshold simply to beat the beep—not advised. But if we add a few seconds to that number, like 4 to arrive at 44, now Stacy has a send-off of 44 seconds for every 50, or 1:28 per 100. This session will be a little harder than the 10x100 on 1:30, and maybe that’s what Stacy needs at the moment. Here is a rough breakdown of RM numbers and their relative difficulty:

RM0: very difficult or 9-10/10. Swimmer has to consistently swim faster than threshold to make interval, so the set has to be short, like only 3-4 intervals. If you’re trying to train a swimmer’s anaerobic ability or VO2max, this is what you’d use.

RM1: very difficult, probably still close to 9/10. Only advisable in small doses. If you’re trying to train a swimmer’s anaerobic ability or VO2max, this is what you’d use.

RM2: difficult, or 8-9/10. If a swimmer is swimming at threshold pace, they’ll only get 2” rest per 50. Imagine swimming a set of 10x200 at CSS with only 8” rest between each interval. Yowza.

RM3: hard but doable, a good number if you’re trying to stimulate CSS/threshold. Probably 7-8/10.

RM4: comfortably hard, in the 6/10 range. Good for long aerobic sets and stimulating the endurance system.

RM5: endurance. The swimmer can swim 5” slower than threshold and still rack up 5” rest per 100. Great for long intervals or pull sets.

Conclusion

Far too many swimmers and triathletes don’t understand the pace clock and what a powerful too it is. They use their watches instead, sadly, which dissociate them from the workout. If you know your threshold pace, know how to use the pace clock, and can manipulate Red Mist style intervals, you are well on your way to mastering effort in the pool, and learning more about what different intensities or sendoffs feel like while swimming. That kind of personal knowledge is worth its weight in GPS watches, since you can put it into play when it counts, on race day.