Training Convenience vs. Race Day Command

How focusing on “convenient” lets you down on race day

by Chris Bagg

Over the last year and a half, I’ve gotten the opportunity to do some work on a podcast series about the rise of AI in K-12 education. One of the chief issues with AI in education is that generative AI such as ChatGPT can convincingly and compellingly complete homework for students, allowing those students to bypass the learning necessary to completing assignments on their own. While many are quick to blame students, the issue lies more with the companies producing generative AI and an educational system that says it values learning but instead only rewards grades and scores—in such a climate that prioritizes outcome over process, it’s no wonder that students would pick the safe way out. Along the way, the companies that produce AI get more market share and more value, and our schools graduate students who have the trappings of education, instead of actual learning.

This article isn’t going to be about AI training plans in endurance sports (I say “training plans” because there is no such thing as AI coaching—more to come on that topic on another day), but it IS going to be about how a similar process is happening in endurance sports, robbing athletes of the chance to truly understand their own bodies, their own efforts, and how to use devices to support—not replace—the mastery that truly great endurance athletes are able to display on race day.

In the last twenty years, as technology has shrunk to fit inside our bike computers, watches, stationary trainers, goggles, and sunglasses, the device industry has created hundreds of products that purport to simplify, clarify, or remove uncertainty from our training. The marketing copy associated with these products is always something like “take the guesswork out of your workouts and race day performance,” or “simply maintain your cadence and the trainer takes care of adjusting your intensity.” The tacit message underlying the marketing speak, though, is something like “buy our product and you can be a mostly passive passenger on the way to picking up your finisher’s medal.”

Is it truly as bad as all that? Maybe not, but I am heeling it up in pursuit of a greater good. The endurance industry seems to think that athletes want someone or something to do their thinking, pacing, and analyzing for them, and the dream/nightmare they are peddling is that you don’t really have to be involved in your training. You can establish some goals, sync your device to the TrainingPeaks/Strava/Garmin/Wahoo/Intervals.icu/MyFitnessPal cumulonimbus cloud, and then mentally check out of the process, while your watch, bike computer, trainer, Oura ring, Whoop strap, and smart goggles chirp, beep, buzz, resist, monitor, and chide you to your goals. The companies all seem to believe that by checking out (coaches call checking out “dissociation”) you as an athlete will enter the mythical “flow state” more readily, as if flow state were a product of some Zen-like disconnection.

If you haven’t already picked up on my tone of voice, I am here to puncture that bubble today. Flow state is not a dissociative state—in contrast it is decidely associative. You are literally so “checked in” that you are experiencing every moment in its fullness, rather than ignoring everything that’s happening around you. Today we’ll talk about how we can still use our devices, but return them to their proper place in our endurance journey.

What Do Device Companies and Social Media Platforms Want?

What Do Process-Oriented Athletes Want?

Why Device Reliance is Fragile

Inputs vs. Outputs

How to Put Your Devices to Work for YOU

What Do Device and Social Media Corporations Want?

You probably know this already, but device companies want to sell devices, and social media companies want your data. The device companies often have websites that also collect your data, which is a benefit to them, but they also want to tie you to their platforms, since more users equals more money in an Internet that exists because of ads. In order to keep you buying their products, device companies have a difficult needle to thread: their devices have to be good enough to avoid customer service disasters, but they also have to wear out on a predictable timeline to create repeat customers.

Social Media companies want users, data, and engagement, so they design their product in ways that gamify and hook users, making it seem crucial to upload the data from your most recent endurance activity.

Neither device nor social media companies care about your performance. They care about the dollars that you represent. It is really important to remember that as we walk through this issue today.

What Do Process-Oriented Athletes Want?

The best athletes in the world are addicted to process, not outcome. Interview high-performers everywhere, from endurance sports to the NFL, and you’ll hear stories of athletes for whom the putative goal (winning) is less important than their drive to figure out how their sport works and how they can optimize their bodies, brains, and emotions to be the absolutely best that they can be. Ironically, this obsessive focus on process often leads to great outcomes, because if you prepare like a champion you are more likely to perform in such a way that leads to success.

To the process-oriented athlete (and ideally you are sensing that process-oriented > outcome oriented), anything that can help track and record our performances is a great tool in our toolbox of performance, but it is no more than that. Process-oriented athletes understand that they have to be prepared for a huge array of situations on race day, and they cannot anticipate all of those situations. So process-oriented athletes do the hard work, in practice, of being intellectually, physically, and emotionally flexible. They understand how their bodies will react in most situations, so when an obstacle presents itself, they have a large array of tools with which to surmount the problem.

Device companies, as I pointed out above, don’t care about your performance—they care about being indispensable in order to keep you as a customer. So all of their marketing speak is going to try and convince you (as AI does for students) that you only need them and their product to succeed. If you buy (literally) this myth, you are not only setting yourself up for unforced errors on race day, you’re unlikely to every achieve your genetic potential in the way a process-oriented athlete might. Device companies want to tell you that if you follow the guidance of their products, you can sit back and let the outcomes happen. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Device Reliance is Fragile

No system is 100% accurate, and sport devices are no exception. GPS watches are confused by the decreasing radius turns of a track, wrist-based heart-rate monitoring is wildly inconsistent and unreliable, and all of us have forgotten to charge devices or replace batteries, leaving us on race day without…any data whatsoever.

Devices can’t account for changes in conditions in ways that are actually helpful. If you don’t know that in temperatures over 85° Fahrenheit your heart rate will be *10-12 beats higher at a given pace* than the same pace in 70° weather, you suddenly can’t rely on heart rate that day. Similarly, if you don’t know that your effort is much higher in the heat and you try to run or ride the same pace you would in more temperate climates, you will blow up long before the end of the race.

Need another example? If you do all of your workouts using erg mode on your smart trainer, you are outsourcing learning to your devices. Building the fine control that allows you to target a certain wattage and hold that wattage, even as terrain and fatigue fluctuate, is a crucial skill for succeeding in triathlon or cycling.

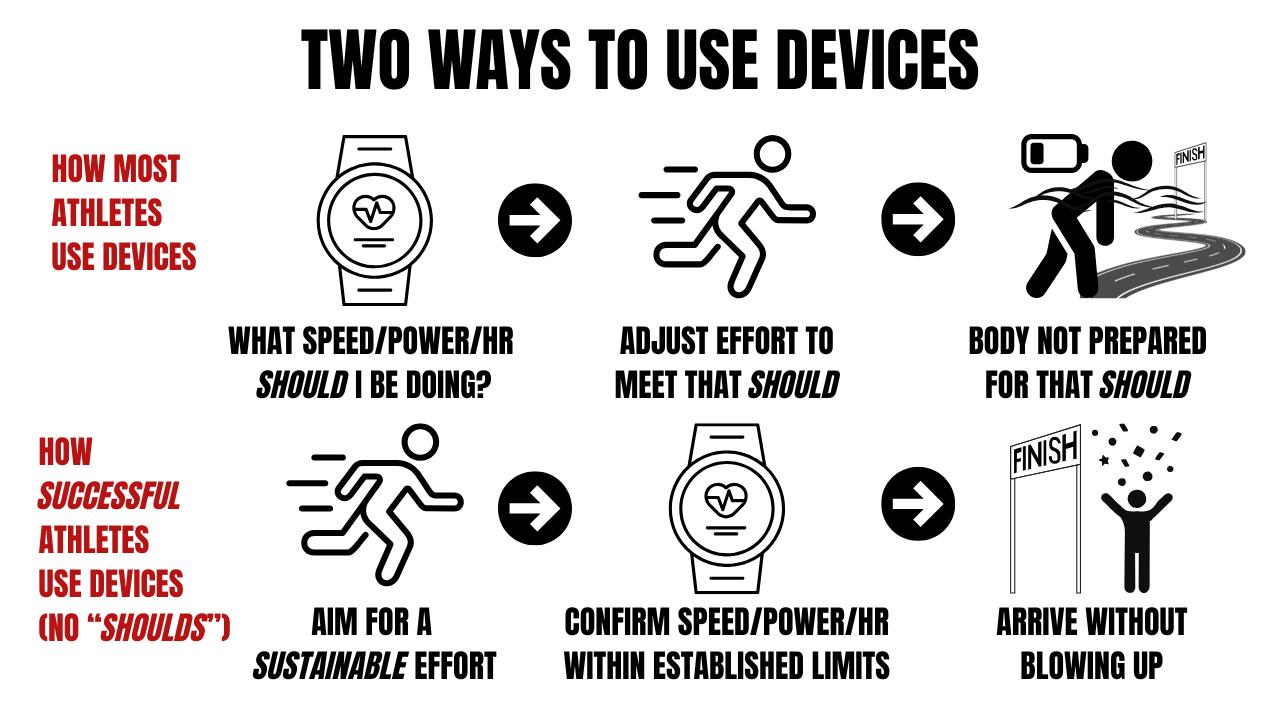

Your “job” as an endurance athlete is managing your effort, across a variety of workout and race-day conditions, so you have the best possible chance at the goal that you have set for yourself. Devices are powerful tools that can help us begin to understand what certain subjective efforts “mean” in terms of objective information such as power, heart rate, and speed/pace, but the issue here is one of description versus prescription. If you are using your device correctly, you use it descriptively, i.e. the device helps you understand what you just did or what you are currently doing. If you use a device prescriptively, on the other hand, you are slaving yourself to its fickle demands: if you’ve trained to run a 1:32 half-marathon and you’ve only trained in conditions under 70°, you are in for a rough day if you try to run 7:00/mile pace on a 90° day. Yet athletes do this all the time and are confused when they blow up. All they had to do was feel the additional strain the heat was causing in their body, see the elevated heart rates they were experiencing, and slow down until they felt the sensations they experienced in their training. Will they get their 1:32 half-marathon that day? No, they won’t, but physics have rarely cared about human aspirations. And instead of walking the second half of the race they get the satisfaction of knowing that they were flexible on game day and got the best performance the conditions would allow.

Outputs vs. Inputs

Before we had training devices, there were two ways to track effort and performance: your subjective feelings and your speed. Speed could even be a little difficult, because you would need a way to keep track of time, and you would have to know the exact distance of your effort or interval. Tracks and pools and velodromes helped with this issue, because the distance was set (400m, 25/50m, or 250m…usually) and someone nearby had access to a stopwatch. The problem, however, is that speed is the most fragile of metrics we use. On a track or in a pool speed is more reliable, because tracks are flat and pools have lane lines to keep you going straight. But if you have ever tried to hold a consistent speed while running or cycling up and down hills, or in the wind, or swimming in a choppy ocean you know that 7:00/mile on a flat track is very different than 7:00/mile on a technical trail with elevation changes in 90° weather. Too many variables impose inconsistency on speed.

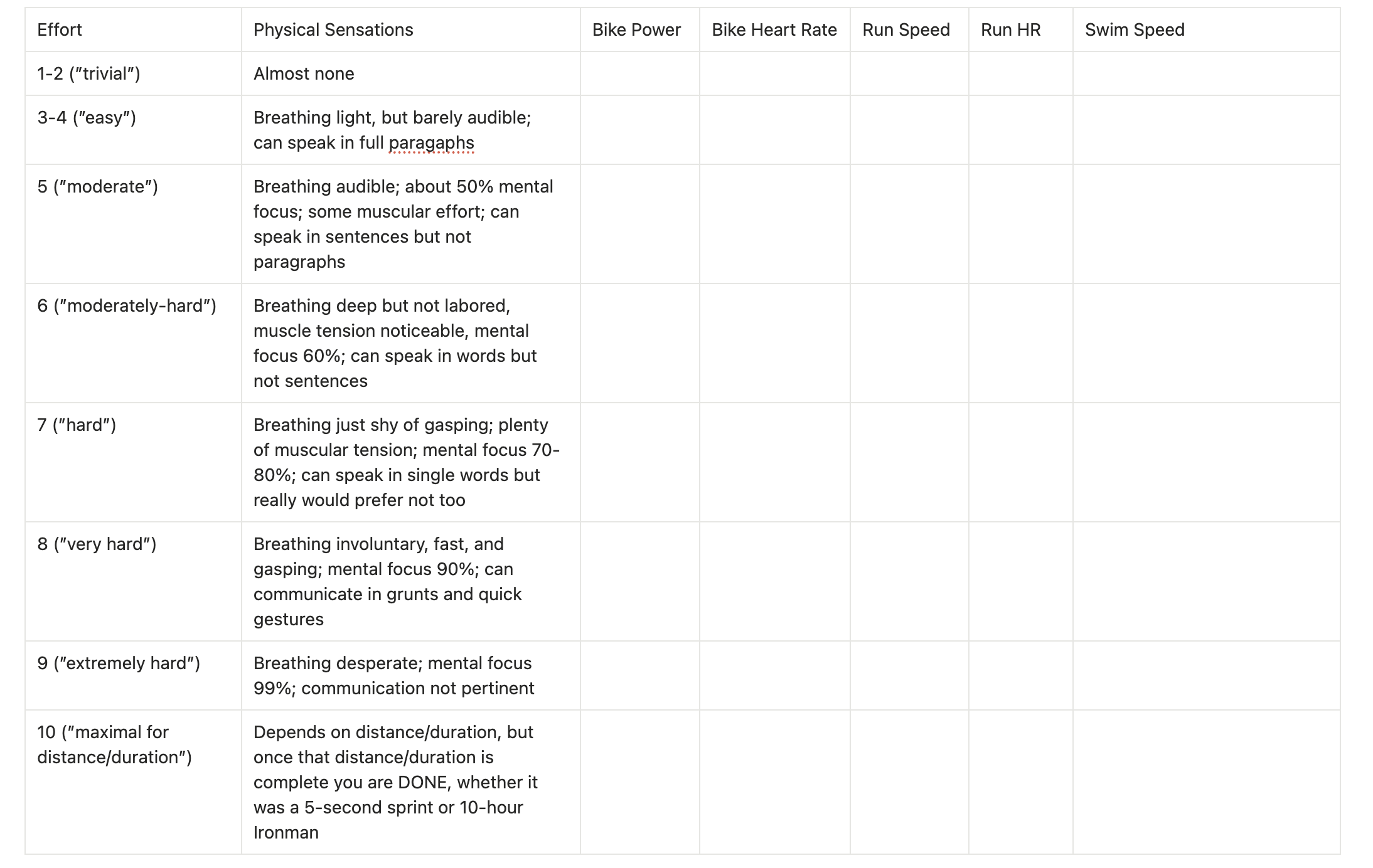

On the other hand, subjective feelings are helpful, but if we have no way to standardize those feelings into useable data, they don’t mean much. Your job, as an athlete, is to learn what a certain subjective effort (”Easy,” “moderate,” “hard,” “extremely hard”) means in terms of objective data such as heart rate, power, or speed if we can account for all the variables—which is why tracks, pools, and velodromes exist! When Roger Bannister was trying to break the 4:00 barrier for the mile, he needed to know what speed he was going based only on the feelings in his body. The interplay of objective and subjective teaches you something about both sides of that equation, and you begin to form a database in your head of what different sensations mean in terms of objective output—this is the crucial experience that makes a great athlete and it cannot be shortcut.

The problem is that device companies try to sell you a short cut.

Device companies try to tell you that you don’t need to do any of this work. They say “just use our devices and we’ll take care of the rest.” Unfortunately, as we’ve pointed out above, device reliance is fragile. We know that devices have a place in this situation, but we’ve gotten things backwards, using devices to lead us, rather than a backstop that helps us confirm that what we’re doing is right.

The whole point of training for steady state events such as triathlon (where the goal is less about going fast than it is about slowing down as little as possible) is to know what your body can achieve now, train it to achieve more, and then race in such a way that you would run out of resources ten meters beyond the finish line, regardless of the event distance, which is why you can run a 5k faster than you would run in a marathon. You need to respect the demands of the event and be realistic about what your body can accomplish.

Most athletes, though, do this in reverse. They think there is a pace or power they “should” be able to do (usually arrived at by dubious means and almost never through actual sensible experimentation) and they aim for that power, regardless of any evidence they’ve seen to the contrary. They are putting the cart before the horse, or letting the tail wag the dog. Pick your idiom.

How to Put Your Devices to Work for YOU (Instead of the Other Way Round…)

Your devices should exist as backstops to make sure you don’t make a mistake, NOT drive your behavior. How do we do this?

1. Spend a month training using effort ONLY (this is how every athlete at Campfire starts their journey with us), recording your outputs but never feeling either good or bad about those outputs

2. After a month, you will have formed a pretty solid idea of what inputs result in what outputs. If you ride at 7/10 or “hard,” maybe you generate 300 watts. If you swim at 5/10 effort, maybe that’s around 1:40/100y. And if you run at 2-3/10, maybe that’s usually between 130 and 140 heartbeats per minute. Ideally you record as many outputs as you can: heart rate, power, speed/pace.

3. Do some field testing! For endurance sports, finding out your threshold power/pace/heart rate is usually one of the things we need in order to train effectively. Usually threshold is around 7-8/10, or “hard to very hard,” but not “extremely hard.” Kolie Moore over at Empirical Cycling has a great way of identifying your threshold: “An effort above which you fatigue quickly, and below which you fatigue slowly.” There are lots of ways to test threshold, some better than others, but again, aim for that *effort* and then see what output you get.

4. Now that you have a threshold power/pace/heart rate, we can start forming a more complete picture of inputs and outputs. Make yourself a chart like the one below and start recording some of your outputs

Conclusion

Now you have the full picture of ALL your inputs (subjective effort) and the outputs (objective metrics) those inputs result in. Congratulations! You have begun to move in the direction of putting things back into the right order. When we race or train, we are in control of two things: our attitude and our effort. Here at the end of this monster post, you now know that effort = input. The output related to that input, though, is NOT in your control:

Are you running uphill or down?

Is it very hot out? How about cold? Is it humid?

Are you pedaling into a headwind or with a tailwind? Are you drafting or breaking the wind for others?

How choppy is the water?

Are you hydrated and fed?

Are you happy, anxious, or angry?

Are you thinking about what you can do or are you thinking about what others are doing?

Now, a device company will tell you that this is too much information to keep track of, that you need some help (condescending head pats go here).

You do NOT need help. You have spent a lot of time figuring out these different inputs and their resulting outputs. You can also start forming a picture of how the outputs change due to different conditions, external like weather or internal like hydration or thoughts and feelings.

A masterful athlete constantly keeps all of this information close at hand without letting it overwhelm them. Your job, as you train for races, is to assemble as much information about yourself, your equipment, and your event. Then, on race day, you go out and let all of this information guide you.

Your devices are only a part of that information, not all of the information. Let’s return them to their proper place in our training and racing.